Note from mom, found posthumously.

A note from a father to a son, posted on FCKH8.com’s Facebook page (and their Twitter feed), has gone viral and is going viraler even as you read this. It was written by a dad to his son after he overheard his son talking to a friend about how to come out to his parents. I first saw it at The Good Men Project, in a post by William Lucas Walker. According to Parentdish, “FCKH8.com founder Luke Montgomery said the letter was mailed to them by Nate, a high school student in Michigan.” Bless Nate; bless Nate’s parents.

These publicly shared moments, in which straight parents express their love and understanding of their gay children, are becoming more and common, thanks to the concurrent (and not at all coincidental) growths of social media and mainstream support of LGBT people. They’re also bittersweet. Sweet, surely life-changing (and sometimes life-saving) for the kids of these parents, who are hearing them now. Bitter for those of us whose parents neither knew nor understood this hugely consequential facet of us, or at least not at the time we were young, vulnerable, and in deepest need of their understanding and approval.

I say this as one such who, at the time, considered myself lucky. I felt sure that my parents wouldn’t have disowned me, had they known the truth about my first love. But what they would do or say, I didn’t quite know. I sensed that they would be disappointed and not understand, which was more or less the case.

After five years together with her, and using the invite to our commitment ceremony, I told them that the gal they knew to be my best friend and roommate was also my love. I was 25; our commitment ceremony was the first (and for years to come, the only) same-sex commitment ceremony I had ever attended. But I knew they existed. I asked my parents to come to what would be a modest event in a friend’s living room. My mother didn’t come. My father brought a case of champagne, but left before the first guests arrived. “Stay, Dad. You know everybody. It’s going to be really nice.” He begged off, and left.

My then-partner’s parents, first-generation Californians whose parents had emigrated during the Mexican revolution, were old fashioned, devout Catholics. She and her siblings all made their First Communions, and a combination of tradition and familia bound them all together. When my partner said that she feared her mother would spend days and nights lighting candles at church and praying for her if she came out, she wasn’t really exaggerating.

She came out to her mom when, after our break-up, she couldn’t conceal her broken heart.

For my part, I spent the next six years following my coming-out trying to help my mother toward understanding me. No, I would tell her, when I broached the subject, I did not become a lesbian after having had a terrible relationship with a boy; in fact, the worst injury I’d had at any boy’s hands was not being picked for the co-ed softball team in P.E.

I considered it a win when my graduate school department sent me to give a paper at Stanford University, the title of which was “A More Queerly Defined Multiculturalism.” They went on to pay my way to give several more papers at several other university conferences, each a part of the burgeoning new field of LGBT Studies. Whether or not she fully felt comfortable with my openness about something she grew up considering an error, I was actually given travel money by my university to talk about it. And I felt that helped make a difference for her.

We were making incremental progress. And then, before I turned 31, she died of breast cancer.

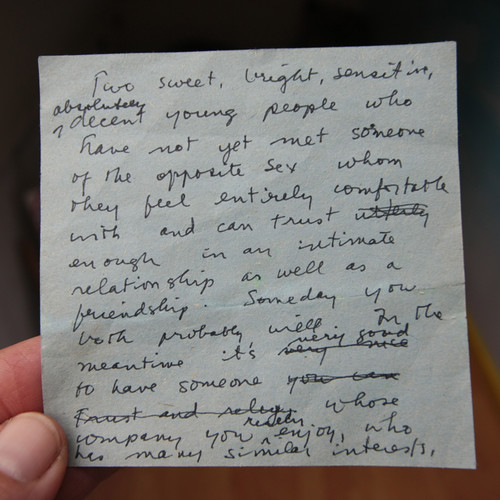

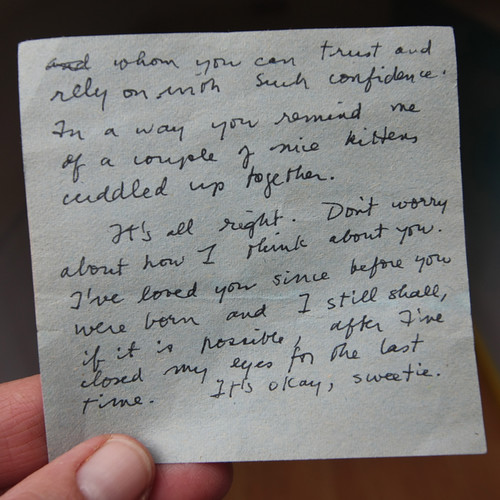

I found the note pictured above (and transcribed below) after she died, toward the back of one of her dresser drawers, under a box of jewelry. She wrote it evidently after having found my first sweetie and me asleep together in my bedroom. But she never gave it to me. I’m not sure what would have changed, had she done so. Probably a lot.

Two sweet, bright, sensitive, absolutely decent young people who have not yet met someone of the opposite sex whom they feel entirely comfortable with and can trust

utterlyenough in an intimate relationship as well as a friendship. Someday you both probably will. In the meantime it’svery nicevery good to have someoneyou can trust and relywhose company you really enjoy, who has many similar interests,andwhom you can trust and rely on with such confidence. In a way you remind me of a couple of nice kittens cuddled up together.It’s all right. Don’t worry about how I think about you. I’ve loved you since before you were born and I still shall, if it is possible, after I’ve closed my eyes for the last time. It’s okay, sweetie.

Oh. Crying.

This made me cry. Thank you for sharing it.

Oh my goodness…what a story. Love and families are so complicated. I love the way your mother could see the love and affection between you two, even if she struggled to understand in other ways.

Thank you, LD, for sharing that most intimate letter from your mom; acceptance is all we really want from those we love and with that the hope they love us enough to hang in with us.

Crying here as well. It sounds so much like my grandmother with whom I have always been very close, who does not understand my being trans but is always sure to remind me that she loves me and the important thing is to stay in touch. My parents tried to starve me out of it or have me placed in inpatient care, but my grandma wants me to know that I am loved.

This is beautiful. So wonderful that you can share something like this.

wow….