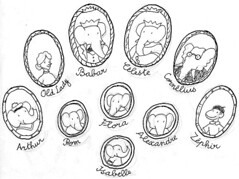

Color-your-own Babar family, courtesy L. de Brunhoff.

Okay, so what was I doing not knowing that the dear, beloved Babar stories open with (a) the shooting death of his mother, and roll onward inexorably toward (b) the poison mushroom-induced death of the King of the Elephants, and (c) the marriage of Babar to his cousin Celeste? Since when was Celeste his cousin?! How did I not remember that?! And I haven’t even gotten to (d) the romanticizing French colonialism thing yet!

Parenthood, apparently, entails the shocking revisitation of any number of submerged traumas from one’s own childhood, one by one.

To answer my own questions, I did a little armchair sleuthing, and discovered that it was not the illustrator Jean de Brunhoff but his wife Cecile de Brunhoff who came up with the original tale; her husband then went on to illustrate and proffer it to a family friend in the publishing business. One must imagine that (a) she sure wanted her kids to appreciate her? lest she up and get shot by cruel hunters one day?; (b) she sure wanted her kids to lay off the ‘shrooms; (c) hooking up with one’s cousin was not, in 1930s France, the creepy untoward thing we consider it today; and (d) critiquing colonialism, as opposed to romanticizing it, was clearly not en vogue for your average white Western mid-century artist.

Further notes to the above irregularities about the tale: (a) Bambi, released 15 years after the publication of the first of the Babar stories, struck the same ominous founding note; clearly it is just be too hard to resist this kind of mother-loss terrorizing in children’s tales. Fortunately Mme. de Brunhoff managed not to get shot, instead living to the enviably ripe age of 99, beloved, one must imagine, by her three sons, her four grandchildren, and her four great-grandchildren. Next, (b) it’s quite true that folk tales have as their common function to inform children about and properly terrify them of the world’s dangers (c.f. Grimm’s Fairy Tales, and Der Struwwelpeter, or Shockheaded Peter). “When the bough breaks, the cradle will fall/ and down will come baby, cradle and all.” And so forth. Furthermore, (c) maybe the French are just different from us. The film Cousin, Cousine, featuring an intra-cousin love story, came out in the fairly recent mid-1970s, after all. The whole topic is plain eeby-jeeby so I’ll just stop there.

Finally, (d) Herbert Kohl, in a 1995 book, asks the question Should We Burn Babar? I’ll have to re-read the Babar Å“vre, plus Kohl’s book, before I can fairly answer that question. Though I’m more inclined to look for insight to Jack Zipes’ Fairy Tales and the Art of Subversion, since I’m anti-censorship on General Principle, and the idea of burning any book, even in jest, seems about as savory as shooting an elephant’s mother out from under him.

Jean de Brunhoff’s son Laurent, took up the pen and the Babar legacy when the de Brunhoff pere died at a very young 37, of TB. Laurent evidently greatly regretted his own early depictions of Africans, and decided for instance that Babar’s Picnic never be reprinted because of this. Random House, who has the rights to the franchise, has decided to continue to publish Travels of Babar, though. I learned this from Alison Lurie’s December 2004 New York Review of Books survey of the entire Babar panoply, including five works of criticism about it. She notes that the current Amazon description of Travels with Babar calls it “as far from politically correct as you can get.” Looks like I have some research ahead of me.

Let us leave the whole Pandora’s box of elephants with parting wisdom from Ashleigh Brilliant, whose post card witticisms delighted my mother thirty years ago, and still delight me. He has one with a sketch of Rodin’s the thinker, accompanied by the thought: “It’s all very simple, or else it’s all very complex, or perhaps it’s neither, or both.”