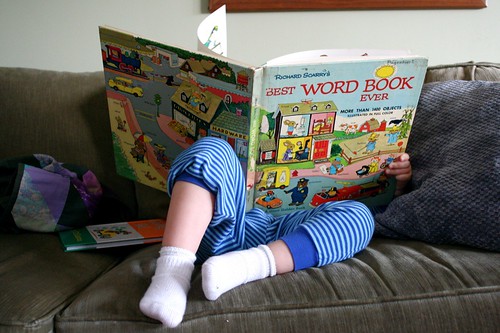

Richard Scarry’s Best Word Book Ever delighted my sister and me when we were little, and it’s continuing to see a lot of action our kids’ generation, too. But after wiping the dust off my memories about the book, I find a fascinating time capsule of popular culture, some of it charming, some not so charming.

This page from rotten dot com (an archive of disturbing illustration) provides a thorough biography of Scarry, including discussion of complaints over the stereotypical and demeaning depcitions of female and “ethnic” characters. (Eventually all the characters he drew were animals, but he drew them in clothing which clearly marked them. Then there were all those vocabulary words.) At the end of the 1960s,

Random House urged him to change with the times, and he wasn’t too difficult to persuade once he learned sales were being affected. His Best Word Book Ever was still his number-one bestseller, and it was accused of being the worst offender. And so he drew new art, using women workers on the job, and depicting men taking a more active interest in household duties.

Alan Taylor’s Flickr photoset documents some of the revisions made to this book’s original edition (1963, the vintage we have) for its republication in 1991. Fathers pop up in the kitchen, where they had never tread before; “beautiful screaming ladies” hanging out of burning buildings get expunged and replaced with “cat in danger”; and odious ethnic stereotypes are scrubbed.

I don’t have a copy of Busy Busy World from my youth, but if I did, I’d be interested to review after reading this account:

…changing times and buckets of hate mail at Random House suggested that characters like Manuel of Mexico (with a pot of refried beans stuck on his head), Ah-Choo the near-sighted panda bear from Hong Kong, and Angus the Scottish bagpiper were no longer acceptable role models for children.

Yegods! Shades of Babar! Because when you revisit this sweet elephant, you’ll see he’s often adventuring in front of a wince- or nausea-inducing colonialist backdrop. Last July I wrote about a lengthy essay on the Babar oevre in the New York Review of Books by Alison Lurie. In it she charts both the ignominy of this series and the attempt by the author’s son to repair it:

Jean de Brunhoff had drawn caricatured Africans in The Travels of Babar, and they must have seemed a reasonable subject for his son Laurent, who was only twenty-three at the time Babar’s Picnic was written. Soon, however, as people all over the world became aware of the hateful and harmful stereotyping of not only African but Asian and Native American people, Laurent was one of the first children’s book artists to make amends and include realistic drawings of black people in his public scenes.

What’s interesting in both these cases is how, eventually, either the author himself or the author’s offspring has worked to rectify onerous, dated characterizations. It certainly gets me to wondering what social changes will emerge in the upcoming generation, and how they’ll cast a telling light on the books we’re now reading to our kids. Like so many of us in alternative families, I look hard for stories that reflect not just my kids’ family structures, but those of kids in other kinds of alternative families, whether what makes them “different” from the norm has to do with who’s in their family, or how their family came about, or what-all. Because each of us who’s “different” in any way makes more space for “difference” generally, and our kids are definitely aware of that.

In the future, I get the feeling we’ll see more and more depictions of alternative families, in every which way. A lot of literature is already out there (here are just two lists, for LGBT and interracial families). More is sure to follow. But not a moment too soon: every kid needs them, whatever their family looks like.

thanks for the link; my favorite as a kid was What Do People Do All Day, but I can only vaguely remember some things that were left out of the revised edition, like the whole section on coal mining, I think.

We’re fond of Scarry at our house, too, but are also cautious about his older works. Our favorite is probably Cars and Trucks and Things that Go. It includes female workers like Officer Flossie, who plays a fairly major role, and various female construction workers, lumberjacks, and firefighters. Sometimes their gender is indicated by large bows on their heads–not my ideal representation, but I suppose it’s better than drawing bosoms on raccoons and cats. The main family in the story is–not surprisingly–Ma and Pa Pig and their son and daughter, but they take turns driving, and Ma is the one who puts the snow chains on the car when they drive up into the mountains.

Your point about needing more depictions of different family types is an important one, though. I hope someday we’ll expunge the term “alternative families” and just have “families,” of whatever glorious variations exist.

Here, here! I second the motion (on the planned obsolescence of the modifier “alternative”). It’s already technically inaccurate, since it only modifies what’s presumed to be the norm. And as of the most recent census, as you’ve reported, families that aren’t the purported norm of married heterosexual (born bio-male born bio-female) parents of kids they’ve birthed and not adopted, and not blended from previous marriages, etc.) have long since stopped being the majority family configuration.

But old speech patterns sure die hard! In CA, where people of color have been in the numeric majority for a long while (and, as an aggregate, will reach 61% of the population by 2010), the term “minority” still seems to be used by most white people, and even some people of color, to refer to the group of people that are the state’s majority.

Ah, well. Language and the law both seem to always be lagging far behind our lived realities. We’ll all be living them regardless of what they’re called or how well our legal systems recognize them.